cancer council Understanding Brain Tumours

Understanding Brain Tumours

A guide for people with brain or spinal cord tumours, their families and friends

Understanding Brain Tumours A guide for people with brain or spinal cord tumours, their families and friends

First published January 1995. This edition May 2022. © Cancer Council Australia. ISBN 978 0 6452847 5 1

Understanding Brain Tumours is reviewed approximately every two years. Check the publication date above to ensure this copy is up to date.

Editor: Ruth Sheard. Designer: Eleonora Pelosi. Printer: IVE Group

Acknowledgements

This edition has been developed by Cancer Council NSW on behalf of all other state and territory Cancer Councils as part of a National Cancer Information Subcommittee initiative. We thank the reviewers of this booklet: A/Prof Lindy Jeffree, Neurosurgeon, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, QLD; Emma Daly, Neuro-oncology Clinical Nurse Consultant, Cabrini Health, VIC; A/Prof Andrew Davidson, Neurosurgeon, Victorian Gamma Knife Service, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre and Department of Neurosurgery, Royal Melbourne Hospital, VIC; Beth Doggett, Consumer; Kate Fernandez, 13 11 20 Consultant, Cancer Council SA; Melissa Harrison, Allied Health Manager and Senior Neurological Physiotherapist, Advance Rehab Centre, NSW; A/Prof Rosemary Harrup, Director, Cancer and Blood Services, Royal Hobart Hospital, TAS; A/Prof Eng-Siew Koh, Radiation Oncologist, Liverpool Cancer Therapy Centre, Liverpool Hospital and University of New South Wales, NSW; Andy Stokes, Consumer. We also thank the health professionals, consumers and editorial teams who have worked on previous editions of this title.

Note to reader

Always consult your doctor about matters that affect your health. This booklet is intended as a general introduction to the topic and should not be seen as a substitute for medical, legal or financial advice. You should obtain independent advice relevant to your specific situation from appropriate professionals, and you may wish to discuss issues raised in this booklet with them.

All care is taken to ensure that the information in this booklet is accurate at the time of publication. Please note that information on cancer, including the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of cancer, is constantly being updated and revised by medical professionals and the research community. Cancer Council Australia and its members exclude all liability for any injury, loss or damage incurred by use of or reliance on the information provided in this booklet.

Cancer Council

Cancer Council is Australia’s peak non-government cancer control organisation. Through the 8 state and territory Cancer Councils, we provide a broad range of programs and services to help improve the quality of life of people living with cancer, their families and friends. Cancer Councils also invest heavily in research and prevention. To make a donation and help us beat cancer, visit cancer.org.au or call your local Cancer Council.

Cancer Council acknowledges Traditional Custodians of Country throughout Australia and recognises the continuing connection to lands, waters and communities. We pay our respects to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures and to Elders past, present and emerging.

cancer

council

Cancer Council Australia Level 2, 320 Pitt Street, Sydney NSW 2000 ABN 91 130 793 725 Telephone 02 8256 4100 Email info@cancer.org.au Website cancer.org.au

About this booklet

This booklet has been prepared to help you understand more about brain and spinal cord tumours in adults.

Many people feel shocked and upset when told they have a brain or spinal cord tumour. We hope this booklet will help you, your family and friends understand how these tumours are diagnosed and treated. We also include information about support services.

We cannot give advice about the best treatment for you. You need to discuss this with your doctors. However, this information may answer some of your questions and help you think about what to ask your treatment team (see page 63 for a question checklist).

This booklet does not need to be read from cover to cover – just read the parts that are useful to you. Some medical terms that may be unfamiliar are explained in the glossary (see page 64). You may also like to pass this booklet to your family and friends for their information.

How this booklet was developed – This information was developed with help from a range of health professionals and people affected by cancer. It is based on Australian and international clinical practice guidelines for brain tumours.1–2

If you or your family have any questions or concerns, call Cancer Council We can send you more information and connect you with support services in your area. You can also visit your local Cancer Council website (see back cover).

Contents

What is a tumour? 4

How are brain tumours classified? 4

The brain and spinal cord 6

Key questions 10

What is a brain or spinal cord tumour? 10

How common are they? 10

What types of tumours are there? 10

What are the risk factors? 12

What are the symptoms? 13

Which health professionals will I see? 16

Brain tumours in children 18

Diagnosis 19

Physical examination 19

Blood tests 20

MRI scan 20

CT scan 21

Further tests 21

Grading tumours 23

Prognosis 24

Making treatment decisions 26

Treatment 28

Surgery 28

Radiation therapy 35

Chemotherapy 39

Targeted therapy 41

Treatments to control symptoms 42

Palliative treatment 43

Living with a brain or spinal cord tumour 45

Rehabilitation 45

Managing seizures 48

Driving 50

Working 53

Looking after yourself 55

Life after treatment 57

Follow-up appointments 58

What if the tumour returns? 58

Caring for someone with cancer 59

Seeking support 60

Support from Cancer Council 61

Useful websites 62

Question checklist 63

Glossary 64

How you can help 68

What is a tumour?

A tumour is an abnormal growth of cells. Cells are the body’s building blocks – they make up tissues and organs. The body constantly makes new cells to help us grow, replace worn-out tissue and heal injuries.

Normally, cells multiply and die in an orderly way, so that each new cell replaces one lost. Sometimes, however, cells become abnormal and keep growing. In solid cancers, such as a brain tumour, the abnormal cells form a mass or lump called a tumour.

How are brain tumours classified?

Brain tumours are often classified as benign or malignant. What it means to have a benign or malignant brain tumour is usually different to what it may mean to have one in another part of the body.

Benign tumours

Many benign brain tumours grow slowly and are less likely to spread

or grow back (if all of the tumour can be successfully removed). But a benign tumour may still affect how the brain works. This can be life- threatening and need urgent treatment. Sometimes a benign tumour can change over time and become malignant or more aggressive.

Malignant tumours

A malignant brain tumour may be called brain cancer. Some malignant brain tumours can grow relatively slowly, while others grow rapidly (see Grading tumours, page 23). They are considered life-threatening because they may grow larger, spread within the brain or to the spinal cord, or come back after initial treatment.

Primary cancer

A cancer that starts in the brain is called primary brain cancer. It may spread to other parts of the nervous system. Unlike other malignant tumours that have the potential to spread throughout the body, primary brain cancers usually do not spread outside the brain and spinal cord.

Secondary cancer

Sometimes cancer starts in another part of the body and then travels through the bloodstream or lymphatic system to the brain. This

is known as a secondary cancer or metastasis. The cancers most likely to spread to the brain are melanoma, lung, breast, kidney

and bowel. A metastasis keeps the name of the original cancer.

For example, bowel cancer that has spread to the brain is still called metastatic bowel cancer, even though the person may be having symptoms because cancer is in the brain.

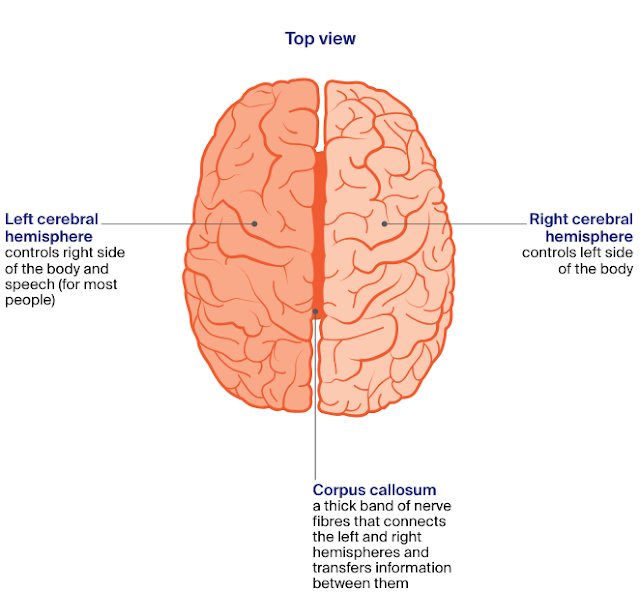

The brain and spinal cord

The brain and spinal cord make up the central nervous system (CNS). This CNS controls how the mind and body works.

The brain – The brain receives and interprets information carried to

it by nerves from the sensory organs that control taste, smell, touch, sight and hearing. It also sends messages through nerves to the muscles and organs. The brain controls arm and leg movement and sensations, memory and other thinking skills, personality and behaviour,

and balance and coordination. The main parts of the brain are the cerebrum, the cerebellum and the brain stem (see pages 7–9 for details).

Spinal cord – The spinal cord extends from the brain stem to the lower back. It is made up of nerve tissue that connects the brain to all parts of the body through a network of nerves called the peripheral nervous system. The spinal cord lies in the spinal canal, protected by a series of bones (vertebrae) called the spinal column.

Meninges – These are thin layers of protective tissue (membranes) that cover both the brain and spinal cord.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) – Found inside the skull and spinal column, CSF surrounds the brain and spinal cord and protects them from injury.

Pituitary gland – Found at the base of the brain, the pituitary gland

is about the size of a pea. It makes chemical messengers (hormones) and releases them into the blood. These hormones control many body functions, including growth, fertility, metabolism and development.

The central nervous system.

The parts of the brain and their functions

Key questions

Q: What is a brain or spinal cord tumour?

A: A brain or spinal cord tumour starts when abnormal cells grow and form a mass or lump. The tumour may be benign or malignant (see page 4), but both types can be serious and may need urgent treatment. Brain and spinal cord tumours are also called central nervous system or CNS tumours.

Q: How common are they?

A: Every year an estimated 1900 malignant brain tumours are diagnosed in Australia. They are more common in men than women. Malignant brain tumours can affect people of any age. About 110 children

(aged 0–14) are diagnosed with a malignant brain tumour each year.3

Benign brain and spinal cord tumours are more common than malignant tumours. The risk of being diagnosed with a brain tumour increases with age.

Q: What types of tumours are there?

A: The brain is made up of different types of tissues and cells, which can develop into different types of tumours. There are more than 40 main types of primary brain and spinal cord tumours. They can start in any part of the brain or spinal cord. Tumours are grouped together based on the type of cell they start in and how the cells are likely to behave (based on their genetic make-up). These groups include glioma and non-glioma tumours. Gliomas are the most common type of malignant brain tumour.

Q: What are the risk factors?

A: The cause of most brain and spinal cord tumours is unknown. As we get older the risk of developing many cancers, including brain cancer, increases. Other things known to increase a person’s risk include:

Family history – It’s rare for brain tumours to run in families, though some people inherit a gene change from their parent

that increases their risk. For example, a genetic condition called neurofibromatosis can lead to mostly benign tumours of the brain and spinal cord. Having a parent, sibling or child with a primary brain tumour may sometimes mean an increase in risk.

Radiation therapy – People who have had radiation therapy to the head, particularly for childhood leukaemia, may have a slightly higher risk of brain tumours, such as meningioma, many years later.

Chemical exposure – A chemical called vinyl chloride, some pesticides, and working in rubber manufacturing and petroleum refining have been linked with brain tumours.

Overweight and obesity – A small number of meningioma brain tumours are thought to be linked to high body weight or obesity.

Mobile phones and microwave ovens

Research has not shown that mobile phone use causes brain cancer, but studies continue into any long-term effects. If you are worried, use a hands-free headset, limit time on

your phone, or use messaging. There is no evidence that microwave ovens in good condition release electromagnetic radiation at levels that are harmful to people.

Q: What are the symptoms?

A: Symptoms you may experience depend on where the tumour is,

its size and how slowly or quickly it is growing. Symptoms can develop suddenly (in days or weeks) or over time (months or years). Many symptoms are the same as other conditions, but see your doctor about any new, persistent or worsening symptoms.

Brain tumours can increase pressure inside the skull (intracranial pressure). Pressure can build up because the tumour is taking up too much space, is causing brain swelling or is blocking the flow of cerebrospinal fluid around the brain (see Having a shunt, page 33). This increased pressure can lead to symptoms such as:

headaches – often worse when you wake up

nausea and vomiting – often worse in the morning or after

changing position (e.g. moving from sitting to standing)

confusion and irritability

blurred or double vision

seizures (fits) – might cause some jerking or twitching of your

hands, arms or legs, or affect the whole body

weakness in parts of the body

poor coordination

drowsiness or loss of consciousness

difficulty speaking or finding the right words.

For information about specific symptoms caused by the location of the tumour, see the diagram on the next 2 pages.

Note: Having a brain tumour is stressful and upsetting. Experienced counsellors, psychologists or psychiatrists can offer coping strategies and ways to manage any mood swings or behavioural changes. Call Cancer Council for information or support.

Nerve and other tumours

Symptoms of tumours starting in the brain’s nerves (cranial nerves) depend on the affected nerve. The most common nerve tumours are vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas). They can cause hearing loss, dizziness and balance issues. Vestibular schwannomas are usually benign. Tumours of the pineal gland (deep within the brain) are very rare and usually classified as neuroendocrine tumours.

Q: Which health professionals will I see?

A: Your general practitioner (GP) or another doctor will arrange the first tests to assess your symptoms. If these tests do not rule out

a tumour, you will usually be referred to a specialist, such as a neurosurgeon or neurologist. The specialist will examine you and arrange further tests.

if a tumour is diagnosed, the specialist will consider your treatment options. Often these will be discussed with other health professionals at what is known as a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting. During and after treatment, you will see a range of health professionals who specialise in different aspects of your care.

Brain tumours in children

and tumours in the lower or back part of the brain, which control

sleep/wake functions, movement and coordination.

Prognosis

In general, children diagnosed with a malignant tumour will have a better outlook than adults. In many children, treatment will cause signs of the cancer to improve

Because a child’s nervous system is still developing, some children may have physical, behavioural or learning difficulties due to the

tumour and/or treatment. These might not show up for several years.

Health professionals to see

Doctors who specialise in treating children with brain and spinal cord tumours are called paediatric oncologists. After 16 years of age,

some teenagers may have treatment in an adult ward. Or they may be

looked after by an adolescent and young adult multidisciplinary team.

Some hospitals have music, play or art therapists, to help children cope with the side effects of treatment Most hospitals have occupational therapists, physiotherapists and social workers, and some may have a child life therapist.

Treatment

Talk to your child’s medical team about treatment options, what to

expect and your concerns.

Support

The hospital social worker can offer practical and emotional support, and suggest support services. Cancer Hub can link you to organisations that support families, young adults and children affected by cancer – including Canteen, Camp Quality and Redkite. visit cancerhub.org.au

▶ See our Talking to Kids About Cancer booklet or our

“Explaining Cancer to Kids” podcast episode.

Diagnosis

The doctor will ask about your symptoms and medical history, and do a physical examination. If they suspect you may have a brain or spinal cord tumour, you will be referred for tests to help confirm the diagnosis.

Physical examination

Your doctor will assess your nervous system to check how different

parts of your brain and body are working, including your speech,

hearing, vision and movement. This is called a neurological

examination and may include:

• checking your reflexes (e.g. knee jerks)

• testing the strength in your arm and leg muscles

• walking, to show your balance and coordination

• testing sensations (e.g. if you can feel light touch or pinpricks)

• thinking exercises, such as simple arithmetic or memory tests.

The doctor may also test your eye and pupil movements, and look into your eyes using an instrument called an ophthalmoscope. This allows the doctor to see parts of the eye and its function – including your optic nerve, which sends information from the eyes to the brain. Swelling of the optic nerve can be an early sign of raised pressure

inside the skull.

Blood tests

You are likely to have blood tests to check your overall health. Most brain and spinal cord tumours cannot be found or monitored by a blood test. However, blood or special urine tests can be used to check whether the tumour is producing unusual levels of hormones, for example, if the pituitary gland is affected (see page 14).

MRI scan

Your doctor will usually recommend an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan to check for brain tumours and to help plan treatment.

An MRI scan uses a powerful magnet and a computer to build up detailed pictures of your body. Let your doctor or nurse know if you have a pacemaker or any metallic object in your body (e.g. surgical clips after heart or bowel surgery). The magnet can interfere with some pacemakers, but newer pacemakers are often MRI-compatible.

For an MRI, you may be injected with a dye (known as contrast) that highlights any abnormalities in your brain. You will then lie on an examination table inside a large metal tube that is open at both ends. The test is painless, but the noisy, narrow machine makes some people feel anxious or claustrophobic. If you think you may get upset, talk to your medical team before you go for the scan. You may be given medicine to help you relax or be able to bring someone into the room for support. You will have headphones or earplugs and you can press a distress button if you are worried at any time. An MRI takes 30–45 minutes.

The pictures from an MRI scan are generally more detailed than pictures from a CT scan (see next page).

CT scan

Many people may have a CT (computerised tomography) scan, or it mayb e used if you are unable to have an MRI. This scan uses x-rays and a computer to create detailed pictures of the inside of the body. Sometimes a dye (known as contrast) is injected into a vein before the scan to help make the pictures clearer. The contrast may make you feel hot all over and leave a bitter taste in your mouth. You may also feel like you are going to pee. These sensations usually only last a couple of minutes.

The CT scanner is a large, open doughnut-shaped machine. You will lie on a table that moves in and out of the scanner. It may take about 30 minutes to prepare for the scan, but the actual test takes only about 10 minutes and is painless.

Note:

Before having scans, tell the doctor if you have any allergies

or have had a reaction to dyes or contrast during previous

scans. You should also let them know if you have diabetes

or kidney disease, or are pregnant or breastfeeding.

Further tests

You may have some of the tests listed below to find out more

information about the tumour and help your doctor plan treatment.

MRS scan – An MRS (magnetic resonance spectroscopy) scan is a

specialised type of MRI. It is sometimes done at the same time as a standard MRI, but is more often used to check if a tumour has grown back after treatment. An MRS scan looks for changes in the chemicals in the brain.

MR tractography – An MR (magnetic resonance) tractography scan helps show the message pathways (tracts) within the brain, e.g. the visual pathway from the eye. It may be used to help plan treatment for gliomas.

MR perfusion scan – This type of scan shows the amount of blood flowing to various parts of the brain. It can also be used to help identify more features of the tumour, or may be used after treatment.

SPET or SPECT scan – A SPET or SPECT (single photon emission computerised tomography) scan shows blood flow in the brain. You will be injected with a small amount of radioactive fluid and then your brain will be scanned with a special camera. Areas with higher blood flow, such as a tumour, will show up brighter on the scan.

PET scan – For a PET (positron emission tomography) scan, you will be injected with a small amount of radioactive solution. Cancer cells absorb the solution at a faster rate than normal cells and show up brighter on the scan.

Lumbar puncture – Also called a spinal tap, a lumbar puncture uses a needle to collect a sample of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the spinal column. The fluid is checked for cancer cells in a laboratory.

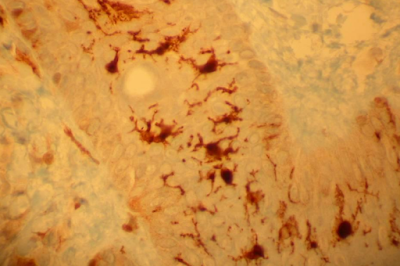

Biopsy – If scans show an abnormality that looks like a tumour, some tissue may be removed and tested. During a biopsy, the neurosurgeon makes a small opening in the skull and inserts a needle to take a small sample. Or they may take a biopsy through your nose. A biopsy may also be taken during surgery, while the neurosurgeon removes as much

of the tumour as possible (see pages 30–31). A specialist doctor called a pathologist will examine the tissue under a microscope for signs of cancer and to work out the specific type of tumour.

Molecular testing – A pathologist will run special tests on the biopsy sample to look for specific changes in the genes of the tumour cells (called molecular markers). These gene changes may happen during a person’s life (acquired) or be passed through families (inherited, see page 12). The test results can help identify the features of the tumour

so your doctors can recommend the most appropriate treatment. Ask your doctor about genetic testing.

Grading tumours

The tumour will be given a grade based on how the cells look compared to normal cells. The grade suggests how quickly the cancer may grow. The grading system most commonly used for brain tumours is from the World Health Organization. Brain and spinal cord tumours are usually given a grade from 1 to 4, with 1 being the lowest grade and least

aggressive, and 4 the highest grade and most aggressive. Unlike cancers in other parts of the body that are given a stage to show how far they have spread, primary brain and spinal cord tumours are not staged, because most don’t spread to other parts of the body.

Grades of brain and spinal cord tumours

grade 1 These tumours are low grade, slow growing and benign.

grade 2 These tumours are low grade and usually grow slowly. They are more likely to come back after treatment and can develop into a higher-grade tumour.

grades

3 and 4 These tumours are high grade, faster growing and malignant. They can spread to other parts of the brain and tend to come back after treatment.

Prognosis

Prognosis means the expected outcome of a disease. You may wish to discuss your individual prognosis and treatment options with your doctor, but it is not possible for anyone to predict the exact course of the disease.

Several factors may affect your prognosis, including:

• the tumour type, location, grade and genetic make-up

• your age, general health and family history

• whether the tumour has damaged the surrounding healthy brain tissue

• how well the tumour responds to treatment.

Both low-grade and high-grade tumours can affect how the brain works

and be life-threatening, but the prognosis may be better if the tumour is

low grade, or if the surgeon is able to safely remove the entire tumour.

Some brain or spinal cord tumours, particularly gliomas, can keep

growing or come back. They may also change (transform) into a higher-

grade tumour. In this case, treatments such as surgery, radiation therapy

and/or chemotherapy may be used to control the growth of the tumour

for as long as possible, relieve symptoms and maintain quality of life.

“My wife Robyn was diagnosed with grade 4 brain

cancer when she had just turned 50. After getting

a diagnosis like that, you just go into shock for a

couple of days, then you start thinking about how

things will change, you evaluate your life and what

you need to do to help.” ROSS

Key points about diagnosing brain tumours

Symptoms Many people diagnosed with a brain or spinal cord tumour have symptoms caused by the tumour, such as headaches, nausea and vomiting, confusion and irritability, blurred or double vision, seizures or weakness in parts of the body.

Main tests • A physical examination checks how different parts of your brain and body are working.

• You may need a blood test to check your hormone levels (e.g. for pituitary tumours) and overall health.

• Imaging scans, such as MRI and CT, allow the doctor to see pictures of the inside of the brain. You may be injected with a dye before these scans to help make the pictures clearer.

• Other scans assess changes in the brain’s chemical make-up, blood flow in the brain and whether there are active tumour cells.

• You may have surgery to remove a sample of tissue (biopsy) or the whole tumour (resection). The removed tissue will be examined under a microscope and have other tests.

Grade • The tests and scans help doctors diagnose the type of brain or spinal cord tumour you have, as well as its grade.

• The tumour will be given a grade from 1 to 4. The

grade describes how fast the tumour is growing and whether it is benign or malignant.

Prognosis For information about the expected outcome of the disease (prognosis), talk to your doctor.

Disclaimer:

The content provided in this article is for informational and educational purposes only. It is not intended as a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. The author and this website disclaim any liability for any adverse effects resulting from the use of the information presented herein

Comments

Post a Comment